In a First, Study Finds Compliance With Marine Reserve Before Enforcement Began

Numerous factors could explain why fishing in Ecuador’s Hermandad Marine Reserve greatly diminished

When Ecuador declared the Hermandad Marine Reserve in the thriving waters around the Galápagos Islands in January 2022, history suggested that fishing within the new reserve might increase before enforcement ramped up. In similar cases around the world, industrial fleets have rushed to fish newly created protected areas in the time between designation and enforcement.

But in Hermandad, the opposite happened.

New research that will publish in the March 2026 issue of the journal Marine Policy found an 88% reduction in industrial fishing within the new reserve immediately following declaration, even though the Ecuadoran government had not yet increased enforcement or approved a management plan (officials did both in 2023). These remarkable findings defy typical patterns observed in other marine protected areas (MPAs) and offer valuable lessons for global marine conservation.

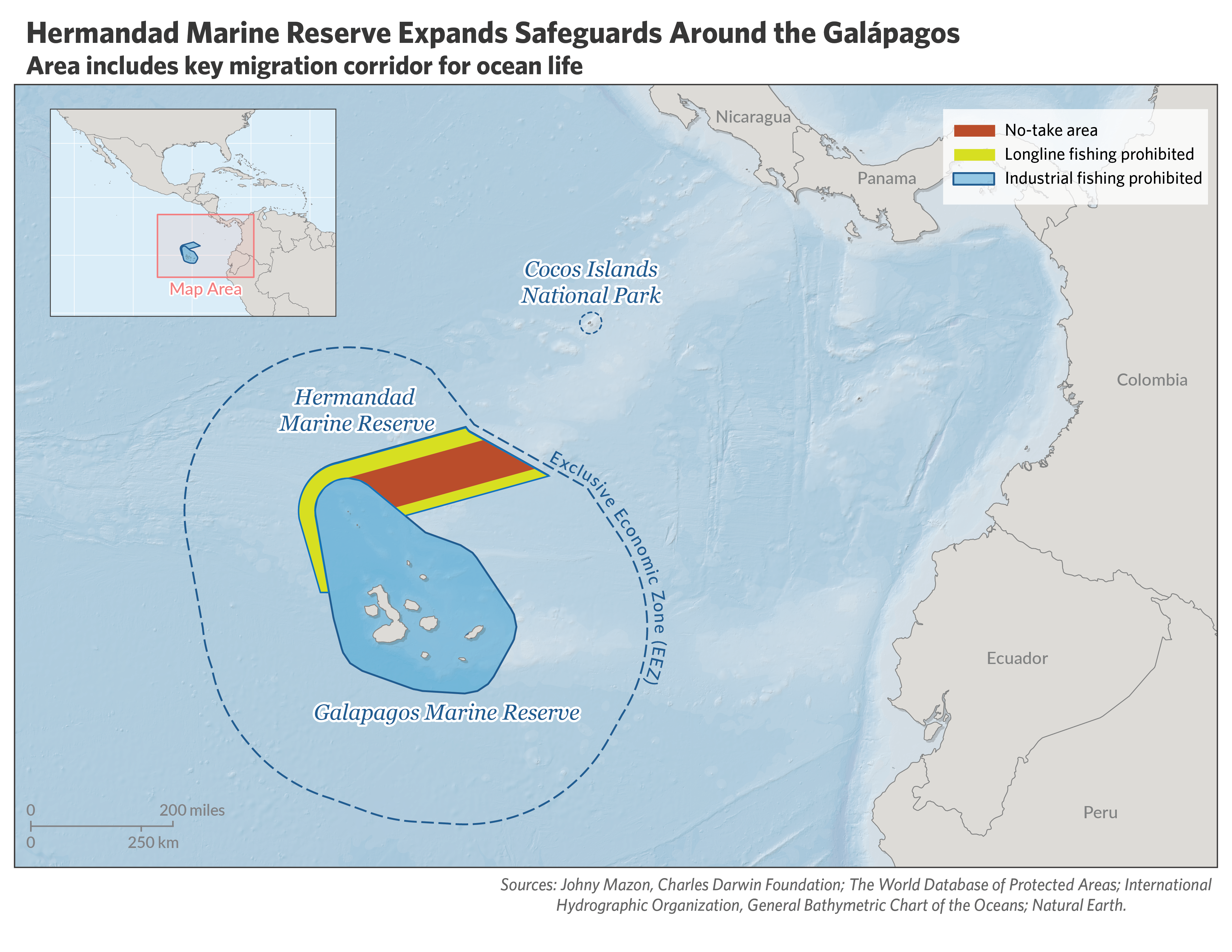

Protection for an underwater highway

Hermandad Marine Reserve spans 60,000 square kilometers (23,166 square miles) of ocean between the Galápagos Marine Reserve and the Costa Rican maritime border northwest of the Galápagos Islands. Half of the reserve is a fully protected corridor used by sharks, whales, sea turtles, manta rays, and many other species migrating between the Galápagos and Cocos Island, Costa Rica. In the other half, some fishing is allowed, but longline fishing is prohibited because of its high bycatch rates of the endangered sharks, sea turtles, and rays the reserve was created to protect. The reserve also supports Ecuador’s commitment to the global goal to protect at least 30% of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030—a pledge known as “30 by 30” that nearly 200 countries agreed to at the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal in December 2022.

In the years prior to the reserve creation, researchers had documented substantial industrial fishing throughout the unprotected waters surrounding the Galápagos Islands. Between 2019 and 2022, researchers found, 145 large industrial vessels from 10 countries logged more than 64,000 hours of “apparent fishing effort”—an estimate of activity, based on the ships’ movements as seen via automatic identification system transponders—in Ecuadorian waters outside of the Galápagos Marine Reserve. More than 90% of this activity was by industrial fleets fishing out of mainland Ecuadorian ports—not by small-scale Galápagos-based vessels, which have long fished mainly to meet the limited demand of their local communities and tourism markets.

The study, led by Dr. Easton White of the University of New Hampshire and co-authored by seven researchers, including Dr. Alex Hearn—whose work is, in part, financially supported by Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy—analyzed satellite-based data from Global Fishing Watch to track industrial fishing activity before and after the reserve’s creation. They found that fishing activity within the new reserve boundaries, which had accounted for about 8% of total fishing in 2021 within Ecuador’s remote exclusive economic zone—which extends about 200 nautical miles from the archipelago’s outermost islands—plummeted in early 2022 not only within the new reserve but also near it.

Researchers suggest that several factors contributed to this unusual outcome. The reserve’s announcement was well publicized internationally, and successful efforts to limit illegal fishing had already drawn global attention to the region. Equally important were the three years of meetings and consensus-building among the government, local communities, artisanal and industrial fishers, and other stakeholders that preceded the declaration.

Broader lessons for global marine conservation

For marine conservation efforts globally, this case provides lessons, including:

- Early and inclusive stakeholder engagement matters. The three-year consensus-building process appears to have been instrumental in achieving voluntary compliance.

- Existing protections create a foundation. The well-enforced Galápagos Marine Reserve appears to have produced a spillover effect, raising awareness—locally and more broadly—about of the ecological and economic benefits of conservation for people and nature.

- Multiple incentives work together. Market-based approaches such as fisheries certification, combined with regulatory measures and reputational concerns help encourage conservation.

- Transparency supports accountability. Publicly available satellite tracking data allows for independent verification of fishing patterns and supports compliance monitoring, even for countries such as Ecuador that lack extensive enforcement resources.

By combining inclusive planning, market incentives, international attention, and transparent monitoring, Ecuador has achieved a strong conservation outcome.

Now, as nations work toward the 30 by 30 goal, Hermandad offers a blueprint worth examining. The path to effective marine conservation may be less about surveillance and sanctions and more about building shared commitment to protecting our ocean’s most critical habitats.

Jen Sawada works on Pew Bertarelli Ocean Legacy.